Martial arts are described as a combat between two people. But what happens if you substitute a human for an animal? The Spaniards have tested this question for centuries.

I remember attending a bullfight as a child and I remember being struck by the distinct nobility of the bull. The music, well-dressed aficionados, and wailing of tears coupled with cheers and guffaws blended into a well-stirred cocktail of aesthetic excess. But it was, after all, the bull that stood at the very heart of the drama. Head raised, hoof sweeping the neatly raked sand, charging at the matador with the full force of a beast intent on killing. The drama of the bullfight is perfect in its simplicity, but the simplicity is feigned for the art of bullfighting is only possible in a highly ritualised form.

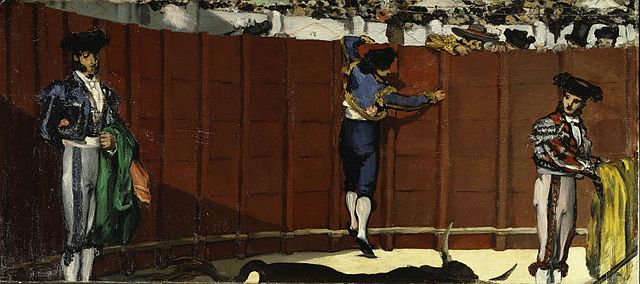

Nobody has done the bullfight more justice than Hemingway in his superb Death in the Afternoon. The ritual of the fight is dissected into its finest parts, taking the reader behind the scenes and back through history to the development and perfection of the art. And indeed it is an art, performed in three distinct acts. The first welcomes the picadors, mounted on horseback and armed with lances that are thrust into the bulls impressive shoulder muscles. The second act sees the banderilleros run at the bull, leap into the air, and place two banderillas (a rounded dowel, seventy centimeters long, wrapped in coloured paper with a harpoon shaped steel point) into the same neck muscle. The intention is to lower the bulls head by relaxing the muscle, no matador being able to reach over the proud head of the oncoming bull should the bull’s neck not be relaxed. In the final act, the matador alone faces the bull, wielding a red cape known as a muleta and a sword, which in the right moment will be thrust into the back of the bull, between its shoulder blades.

The description above is highly simplified and it is difficult to do such a cultural phenomenon justice. But although the rough sketch of the drama has been described above, alone it does not reveal the end or true purpose of the artform. The matador, the man who faces the bull, would ordinarily be at a huge disadvantage should he not know how to dance with the bull. A bull is a clever beast: fast, strong, armed with two sharp horns, and an intelligence which is bred for wreaking havoc. Put differently, he is bred to have a fighting-IQ. A bull must be killed at the end of the fight, for a bull who has fought once and survived is a deadly bull in a second fight, having learned what he is up against. It is in the mastery of the bull, the domination of this formidable opponent by bending him to the matador’s will, that the thrill exists. The matador is in control of the danger into which he puts himself, and the closer he can get the bull to charge and strike, the more impressive he is. Hemingway put it thus:

“…all brilliance is impossible unless the matador has the science and valour to get so close to the bull that he makes him confident and works on his instincts against his inclinations and then, when he has gotten him to charge a few times, dominates him and almost hypnotizes him with the muleta.”

In what sense, then, is this a martial art? Martial arts are ritualised combat, competitions where the valour and determination of the athlete is measured. A bullfight carries all of these aspects, in a way, which, things such as slap-contests like Power Slap do not. In fact, looking at the history of athleticism, we find boxing and wrestling in the earliest cultures, but even earlier yet we find contests with bulls, such as ancient Minoan (2000-1800 BC) events known as bull-leaping. Like any martial artist, the matador walks with an exaggerated pride, proving to the aficionados that he fears nothing. But equally, the bull is the valiant one, and is judged by his courage. A cowardly bull is one that refuses to charge, and while such animals exist, the more common feature is a proud bull who fights to his last breath – outnumbered, outwitted, but not subject to surrender.

Anything capable of arousing passion in its favour will surely raise as much passion against it. – Hemingway

The morality of the bullfight is an entirely different question. The question is held in suspense here, for the fight is largely cultural and those not part of the culture may be excused from moral judgement on something so alien to their own lives. Any moral judgement, of course, should depend on whether or not the bullfight is considered to be an intrinsic evil. If it is evil in itself, one has a moral duty to condemn it. This article is not an attempt to answer this vexed question. But, in order to explore bullfighting as a martial art, we might ask ourselves if there is any virtue to bullfighting, what would it be? I suggest three things.

Bullfighting celebrates courage.

Bullfighting brings together the community.

Bullfighting ritualises violence, giving it a cultural outlet which allows for the violent impulses inherent in man to be displayed without seeping over into violent conflict in society.

There may naturally be many other virtues to the bullfight, but these three are common between boxing, wrestling, bullfighting, and most other martial arts. Bullfighting utilises tactics, much like boxing, Hemingway describing the instinct of the bull to retreat to his chosen “home” or spot in the ring known as a querencia where he feels safe before planning a counter-attack, stating:

“In boxing, Gene Tunney was an example of a counter-puncher; all those boxers who have lasted longest and taken least punishment have been counter-punchers too. The bull, when he is in querencia, counters the sword stroke with his horn when he sees it coming as the boxer counters a lead, and many men have paid with their lives, or with bad wounds, because they did not bring the bull out of his querencia before they went in to kill.”

The bullfight will long continue to fascinate, as well as shock, upset, and mesmerise. In another book, The Sun Also Rises, Hemingway stated “Anything capable of arousing passion in its favour will surely raise as much passion against it.” And so it is with boxing, wrestling, and MMA. If one were to respond to the puritans who denigrate these sports, which have carried civilisation for millennia, one might ask those who are afraid that someone, somewhere is having fun to be safely relegated to their own misery. There, to quote Roger Scruton, they can “bore each other rigid with their futile nostrums for eternal life.”

Lyssna på det senaste avsnittet av Fighterpodden!

Kommentarer