In this magazine, we have covered the history of various martial arts, but over time we will be delving deeper into the history and philosophy of Judo. This is the first piece into the history of one of the world’s most practised martial arts.

The history of Judo might strictly be taken back to the 19th century when Jigoro Kano founded the martial art. This would make it a relatively recent martial art, compared to the many arts that claim a pedigree stretching back into pre-history. Founded on far-off lands, their history seems veiled through the passing of time. With Judo, the case is somewhat straightforward. Judo – as the sport is practised today – does indeed go back to the 1800s, but its roots are much older.

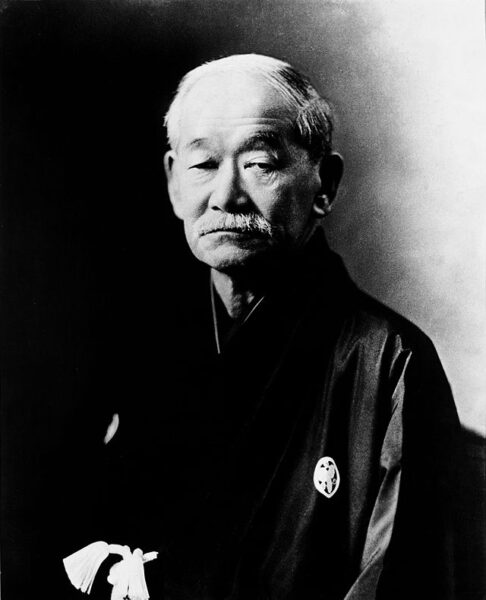

(Right: A Young Jigoro Kano)

SAMURAI

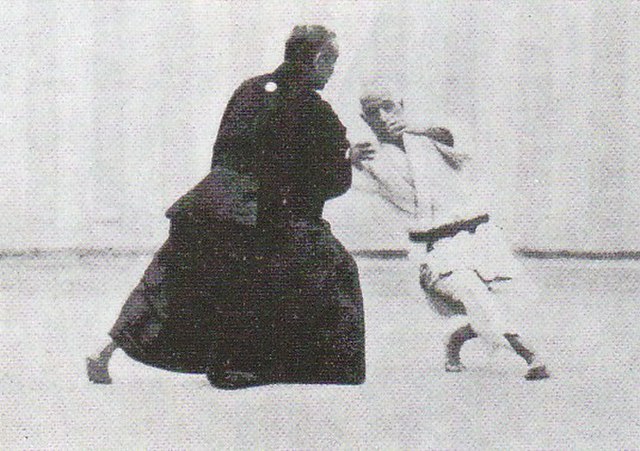

The famed and legendary Japanese warriors, clad in impressive gear and wielding their distinctive swords were masters of swordsmanship, but on top of weapons, they also trained in unarmed combat. The name for this style is jiu-jitsu (not to be confused with what would later become known as Brasilian Jiu Jitsu, which we will get to in future articles, although they are related). The first character – known in Japanese as kanji – is “柔” or “Jiu” sometimes spelt simply as “Ju.” It implies softness or gentlest. The second character in jiu-jitsu refers to a style or art. In other words, it is a gentle art or style. Judo retains the same first character, but “Do” refers to a more holistic approach, akin to a philosophical way of life.

The Samurai has trained in this gentle art in order to excel in combat. But who were they? The Samurai were a military nobility and officer caste which existed in Japan from the medieval period until their abolition in 1876. Their moral and martial code is known as “bushido.” They held a high place in Japanese society, but when the Meiji era commenced in Japan in 1868, bringing modernisation of society, their influence waned. It was in this context that Jigoro Kano was born.

Kano trained in two jiu-jitsu styles: Tenshin Shin Yo Ryu and Kito Ryu. Ryu means ”school.” He began with Tenshin but the aged master, Fukudo, died, leaving another master. Kano continued to study under the new master until he, too, died. Following his death, Kano took up Kito Ryu. Important to the story is the fact that Kano was very small of stature, roughly 157cm, and wanted to find a way of subduing a combatant swiftly, despite his physical disadvantage. Trying the various styles, Kano was able to found his own art which has become known as “Judo.” The official foundation might be said to be the year he founded The Kodokan, the main centre of Judo training, in 1882.

Kano was also a school teacher. He saw the importance of education and Judo is an essential part of Japanese education, as well as it is in many corners of the world where Judo is often the first martial art that children are introduced to. It was this mix of education and martial arts that led Kano to create the mix of martial art and judo philosophy.

PHILOSOPHY

Before we move on to the various types of throws and the art of Judo itself in a future piece, something must be said about the philosophy. Martial arts have always been tied to ideas of virtue, morality, and character. This is what I referred to above as the Samurai code of “bushido.” In the West, we also find a connection between philosophy and martial arts, particularly in the work of Plato and those who followed him and became known as Platonists. Bushido is said to be born out of Neo-Confucian texts but also mixed with Zen Buddhist ideals. Kano created his own code, which every judoka (practitioner of Judo) is expected to live by and uphold in their actions. The code is comprised of eight values: courtesy, courage, honesty, honour, modesty, respect, self-control and friendship.

One might say that these are universal values. Everybody thinks these are good things which one should seek to live by. But the point is not that humans can agree on several good values, the difficulty can be in implementing them. Martial arts, and Judo, in particular, aim to cultivate these virtues – which Aristotle defined as habits that we perfect through repeated actions – and they do so by providing a community where discipline is instilled. Before training, a bow (rei) is expected by everyone in the dojo (the hall of training), and the master is called by a formal title: Sensei. There is a hierarchy based on grades, identified by the colours of the belt, and hierarchy helps to keep the discipline intact.

Martial arts can never be separated from the ethical code. Martial arts aspire to perfect skill, defend the weakest, and improve one’s character. A drunken fight at a bar is not a martial art, as it deviates from the “warrior’s code” or “bushido.” It reflects a lack of character and a lack of control of one’s passions. The person who steps in to stop the fight through his or her superior knowledge of martial arts, however, aims at defending another, him/herself, or calming down a situation. That, in short, is the difference between martial arts and arbitrary violence, and Judo is one superb way of instilling virtues in humans.

Lyssna på det senaste avsnittet av Fighterpodden!

Kommentarer